Journal

Cx72 Interview: Inpatient Press on Tuesday's Child

December 2, 2020

Through Inpatient Press, you often take on taboo subjects: for instance, LA Warman's excellent experimental volume of lesbian erotica, Whore Foods, and Katie Ebbitt's poetry chapbook, Para Ana, which was conceptualized as a response to poet Ana Cristina Cesar's untimely suicide. And Tuesday's Child, of course, is a very special archival document. How did you originally come to re-publish the issues? What was the appeal or draw?

That's a great question: I really like how you set up the context. I read a great book earlier this year called The Art of the Publisher by Roberto Calasso – he's this Italian publisher, very old school guy, who ran Adelphi Edizioni in Milan – and he talks about publishers being one part publicist, one part ringleader, and one part esotericist. He has this idea of "the serpent": that the art of publishing is creating this unified, conjoined creature of all your different books together... when you look at it, it makes sense as a unified, distinct whole. And I think about that a lot: the serpent, this kind of ribbon of books that Calasso talks about, when I choose the projects that I do. We don't have open submissions; it's more whatever happens to fall into our lap.

So that's kind of what happened with Tuesday's Child. I was reading this book, Chaos, by Tom O'Neill... have you ever read it?

No.

We're about to go down some rabbit holes; I hope you don't mind.

I love a rabbit hole.

We're through the looking glass, here. It's a book about, how, essentially, the Manson murders were this part of MK Ultra, connected to drug experiments that were happening in the Haight-Ashbury in '67, '68...

Oh, yeah.

And, so, it's talking about the Manson murders in '69 in the milieu of Los Angeles at the time. And Tuesday's Child is mentioned, as an underground rag that was kind of the first to see this use of Charles Manson as like a leftist hippie demon: as this ball gag that the CIA and the authorities are using to silence anti-war dissent. 'Cause you know, his followers shows up to these houses, they dress like hippies and preach free love and drop acid but murder and paint anti-Black Panther slogans on the walls – obvious race-baiting stuff – there are a lot of similarities with how the FBI would do things with COINTELPRO, with their undercover murders and infiltrations. It's this whole mess, right? And so the author offhandedly brings up Tuesday's Child as like the freak scene’s response to the murders, and it's the only mention of this thing. And I'm like, this magazine sounds sick – it sounds like they're an interesting group of people. It's literally one sentence in this 500 page book. So I look it up, and there's a review on the Paris Review of some of the issues... and it's written by this guy who professes to be a "former magician" –

A reformed magician? [laughs]

He totally shits on Tuesday's Child: "This is a bunch of '60s amateurs running around, playing with their hexes..." And he comes off as extremely annoying, he's reviewing this material, and I can see from the images and the writing that he does not get it. Just like, you've clearly missed the picture, I don't even know what you're doing. And I get on the horn with my friend, Coco Fitterman, who's amazing, and she basically got me the whole document dump of this rag, of Tuesday's Child, which ran for only 7 months – from November 1969 to April 1970.

Just peak Manson time, then.

Right? The craziest – this insane burst. And I think it really encapsulates this interesting admixture... it has these threads of mysticism and politics that you can see evolving in real time. It happened so fast, you know? Because Tuesday’s Child is weekly. And I think we tend to think about things back then as being relatively... slower than now, but it really morphs and changes each issue. It's really remarkable to see how it evolves and adapts to the events as they happen around it. And I was really drawn to that as I was scrolling through the PDF. I thought someone should reissue it. There are lots of archival collections of old, radical zines, but none of them had Tuesday's Child in it. And I thought, this is nuts, because I feel like this is such a gem. That's one of my favorite things about publishing: the incidental, kind of mercurial nature... it's almost hyperreal. I was really struck by the writing, too. The writing is sharp – there are crazy features, lots of interesting investigative angles that really highlight how paranoid everything was. This is one of the most paranoid times in American history, probably only rivaled by now, right?

Yeah. I love fanzines and periodicals... a lot of it is not well archived. People's attitudes towards a lot of those more ephemeral or more mercurial text-forms tends to be a little bit more casual... you might be willing to put out something a little more honest, as opposed to potentially what you might put in something you intended to be more permanent, like a book. Where do you fall on the Manson conspiracy theories?

Oh, my God, you don't even want me to get into this stuff, because this is like a whole other interview. But essentially, it's so crazy – you gotta read this book. The LAPD and Sherriff's Office, all these competing police offices all had a shared idea of what Manson was. People were specifically told not to interact with Spahn Ranch. There were firemen who patrolled, and there were these methed-out hippies with guns saying, "If you come near, we'll shoot you." And they [the firemen] reported it, and the LAPD replied: "Oh, yeah, those guys: don't go there." They had this tacit knowledge of what was happening.

The craziest part of it all was how many times he [Manson] was arrested while on probation and then just released without any explanation. Like, he was caught with drugs and weapons and he always walked. His probation file hasn't even been fully released! When he was let out of jail in '66, he had a parole officer that is selected by the government to pilot this new study: what happens if you have extreme relationships with your parolees, you're really involved with their life? And he would meet with Manson at the Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, where people were freaking out on acid, doing experiments with amphetamines – the Amphetamine Research Project, it's called – and you have all this happening... why is Manson taking meetings here? Why is he piloting this program? And suddenly he shows up in the desert... he's running a car theft ring, sure, he steals credit cards, but no one asks where this insane amount of drugs, and meth, and guns is coming from, right? No one really has any answers around that. I think he was almost certainly primed. The same way you could say Theodore Kaczynski was primed by these MK-Ultra experiments to take a sort of extreme anti-society stance. But it happened on a much more condensed timeline because you have this crazy charismatic sex-cult leader and you give him lots of drugs and tell the authorities to back off... It's just really, really dark.

The thing I love about Tuesday's Child is that this is its beat: getting into the seamy underbelly of Los Angeles and exposing all of the hypocrisies of the free love scene as well as the Establishment. They run stories about CIA infiltration of non-profit food distribution programs. I was reading that article, like, this is nuts. They're trailing agents whose names are lost in time and chasing leads on operations whose files have long since been shredded . And so we get these glimpses into history, you get these little peeks into what's happening – these extremely street-level details... I still can't get over this article about the crash pad. There's this guy smoking a fair amount of dope and watching this crash pad across the street because he thinks it’s a Fed setup to bust people... You think, Oh, this is just paranoia. But then you think about how the CIA did the same exact thing in the Haight-Ashbury... the CIA loved putting together these honeypot setups. It was called Operation Midnight Climax. But at the time you had no “real” proof, no hard evidence like a paper trail. You had stories, what people told you, what you saw. So you get this really conspiratorial view that is both skeptical and also wanting to believe. They're well-versed in the esoteric tradition, but they're also very, like, "Isn't this kind of crazy?" It doesn't have the same naïveté that makes other material from this time seem either irrelevant or otherwise completely detached. This stuff is kind of early Gonzo... I mean, it's really it's own strain of journalism.

Everything you're talking about, it's kind of like, where do I even start with a response? That's the shit that I totally lose it over. I love conspiracy theories, have always loved them, ever since I was a kid. And maybe this specifically is very typical of just being a practicing occultist, but I have this attitude of wanting to hold two truths at the same time – both/and – being open to anything while maintaining this form of skepticism. It's fascinating to track that time period... I've tripped a lot about the Manson murders. I got super obsessed with the whole phenomenon – not with him as a person, obviously, but the entirety of the circumstances surrounding it – when I was in middle school. And then since then... I'm not actively as obsessed, but I've done so much reading on it in my life.

And even just thinking of this notion, his name being something as simple and literal as 'Man Son,' it's very trippy. You know? Like, him growing up in these child penitentiaries, being this discarded child of society, and where that eventually lands. And I know, or used to know, a number of older lesbian feminists. They'd say things like, "Oh, so-and-so [whatever famous writer]? They were a CIA operative." Conspiracies are always happening: whether they're successful is another question. Those things, we don't talk about them in the same way anymore... but those dynamics undoubtedly still exist.

We absolutely don’t talk about this. And that's what's funny about Tuesdays' Child – it's very: "This person's a CIA agent, this person's an operative, this person's working with the Feds." Naming names. And it makes sense: politicians are getting shot in the streets. People are armed. You see in the streets this kind of war coming home.

What was it that the CIA said about the Black Panthers? That their free lunch program was the most dangerous threat to America?

I mean, thinking about Bobby Seale. Bobby Seale wasn't just bound and gagged, he was tortured while he was in his holding during this trial. Tuesday's Child were writing about it, they were tracking it, they were talking to the Panthers about it and organizing with them. They got Eldridge Cleaver to write a communique for the first issue about the actions of the Weather Men. They were positioning themselves to be that kind of counter-culture against the CIA, and that's why there was that paranoia. I think they saw themselves as this kind of asset in a war, of sorts. They have this winking attitude that they are a propaganda piece, almost. That's what I like about them: they definitely have that vibe.

One of the things that I was delighted to learn more about while researching the history of disability advocacy, for instance, was the kind of... So many groups were collaborating with the Panthers. And the Panthers were advocating for so, so, so many groups, in this really radical way. It’s not common knowledge, but the Panthers played an enormous role in the 26-day “sit-in” protests that ushered in the passage of Section 504. It's so interesting... the counter-culture and these social justice movements collided in these surprising ways.

So, you and I were chatting the other day about how this Tuesday's Child is an interesting cultural artifact – because it serves as a documentation at a time when the left was less hardcore materialist, and more mystical. I wondered if you had any further thoughts on that.

I really enjoyed that conversation. I think you're onto something. Because the left is undoubtedly mystical in this interesting way – a lot of left-leaning people would ascribe to mystical leanings, because maybe they're not religious, right? But I was also thinking about this strange dichotomy where the Right also kind of believes in magic, now, as well. Look at how they freaked out over spirit cooking: they see modern art as almost this occult or magical practice. I think that's kind of seeped into the general psyche. We still see a lot of magical thinking today... just think about the energy that was harnessed in wishing for Trump to die. Everyone was really focusing, envisioning this, really trying to make him die.

Or, that moment when Trump's doctors, when he had COVID, said they didn't want to tell America how badly he was doing because they "didn’t want to give any information [to the public] that might steer the course of illness in another direction.” Which is a crazy thing for doctors to say, really.

It's just like, the somatic feedback system. A creature like that just thrives on the public theory. [laughs] I think it's interesting when people do that ["hex him"] – I think it honestly does bother him. People have this proto-conspiracy-theory that Trump instigated the TikTok shutdown to get back at the so-called K-Pop TikTok teens that trolled him by buying up thousands of tickets for his rallies so the stadiums would be empty when he did the Oklahoma rally, and all that. That kind of prankishness is, to me, a sort of magic, a sort of sorcery, in a way; at least you're trying to do these acts to bring about a reality that you want in a very directed, coordinated, and at the same time populous way. That's what the left populous energy needs to harness.

Yes!

In the 60s, you had people trying to levitate the pentagon. You had all this esotericism that is now gone, and has been replaced by... Right now, we see this push where mysticism has become entangled with these market forces: "You like crystals? Maybe you should open up a shop!" It's part and parcel with what it means to engage in that now. I say that as someone who runs a press: I think I run a press a little differently than someone who runs a business would be, but at the same time, there's this inescapable, transactional nature. And I think that's what people do to disembody magic – and when I say magic, I mean a shared social consciousness. The market is the shattering of any kind of social bond that seems, on its face, to be irrational, an uncivilized action.

It's a wild contradiction, right? It is interesting. Even something like astrology: astrology is something that is totally commonplace, acceptable, and normal to talk about... as long as you're being kind of cute about it. But whenever I start talking about the mutated medieval grimoires that are the foundation of traditional astrological magic, some people get super uncomfortable. "What are you talking about," you know?

When you talk about these deep connections... people get uncomfortable when you talk about things that Tuesday's Child does, these things the CIA did, what these operations were, how some Black Panthers were completely eradicated, wiped off the map.

Or MK-Ultra, which is a perfect example of something that is actually... I mean, now it's become synonymous with this even wilder and kind of absurd conspiracy theory involving musicians and the so-called "Illuminati," but in truth, you know [laughs] – the documents that were released on mind control experiments that happened – and that's what they were willing to admit to.

I like where this interview is going. I mean, I'd like to talk about this context that Tuesday's Child situates itself in, by settling into this ironic position. It's very much acid-soaked; it's totally lysergic. They're almost one foot out of the counter-culture, in a way; they really enjoy and embrace it, but their editorial positions and the stuff that they run... it's people kind of investigating themselves in a weird way. Reporting on themselves and the happenings in their scene around them and attempting this kind of prestige journalism. It invites this self-awareness that I think is lacking in a lot of media from that era. I think a lot of it is because Tuesday's Child is happening at the end of the '60s, the turning point of counter-culture, and all that... and all of that was started by the CIA. The CIA was the biggest dosing organization on earth. Not just from MK-Ultra but from the very life of Sidney Gottlieb, who ran MK-Ultra and was the head of the Technical Services Division of the CIA. This dude, I was reading about him: He made assassination pins that you hide inside dimes. He engineered diseased clothing which was used to assassinate an Iraqi colonel. But he also lived his life as a goat farmer in an eco-friendly house reading Eastern literature, and by all means, was mistaken as a hippie sometimes. He was seen as this blueprint... and this is this man who is the establishment: the deepest of the deep state. And he loved to dose people. He spread this kind of weird idea that LSD could be used to reprogram the mind, and this impressed upon other people at the Agency.

By the end of the '60s, people were starting to realize that. People were thinking, "Wait a minute. I went to this party in Palo Alto, one thing led to another," and who hosted that party? The CIA funded Timothy Leary from the start. People were beginning to realize that this whole social movement, this thing they were buying into... And I don't say that to condemn the entire scene, but what we popularly think of it as... I don't want to say was consciously concocted by the CIA, but it was basically "their fault." They kind of opened the box: they created the conditions that led to this insane, paranoid, conspiratorial, weed-soaked, burnt out world that was the 70s – that led to Watergate – that led to where we live now. If you do a lot of acid, you get washed out. You feel a bit strung, you lose your spark a lot. I'm not saying it's the worst, but...

No, totally. I was just talking about this the other day, with a friend. Like, "I'm so lucky I got through my teens and early twenties without developing a serious case of schizophrenia, or something." When I was a kid – a very tripped out kid, I'll add – I'd hear adults talking about it, like, you know, "Acid's dangerous." And at the time I felt like, "No way, it's not dangerous, not at all." [laughs] But it is a little dangerous.

It can fry the mind; it can make you paranoid, in a productive sense; you can kind of re-examine and re-initiate yourself... but at the same time... "If you get the message, you can hang up the phone." [laughs] You don't have to hang on the line.

Oh my God, the classic quote, the classic quote.

It really is, though. That's the thing that's so great about Tuesday's Child. Not only is it completely acid-soaked, but they also get into the freak scene, which is amazing... It really explodes in the late issues in the 70s. Tuesday's Child becomes this vehicle for the queer scene; they run a few features on protest movements happening in Hollywood, the classifieds are populated by a queer community chatting back and forth, hanging out on skid row. For this community, conspiratorial thinking... that's the default, right? This is when cops would go into a bathroom, trick you into the stall and arrest you. That's the world that they're inhabiting, they're seeing it and writing about it in provocative and interesting ways. Not just in features, but all over the paper. "Hey, he's a fed, don't go to this guys house," you have this kind of network. Who's this press have to answer to? No one! It's just this rag. They can put in this information that other places, even other free presses, would balk at.

The main thing that it really got me thinking about when I was looking through it was this notion of... There's this Terence McKenna quote that I really love; of course, I was obsessed with him as a teenager [laughs]. He was basically saying that there are conspiracies that happen all the time, but history is a runaway train, and so people are constantly trying to control this world, but the actual results of these conspiracies that are happening are not what is intended. Which I think is the moment that's crystallized in those volumes.

It's true, it's true. And Tuesday’s Child is coming at a time when you have someone like Nixon, who is a very deep-state guy, who's becoming president. Nixon was so involved with the CIA. He was so emblematic of the "Intelligence-Industrial Complex." He got the Paris peace accords delayed in '68. He pushed them back by going through his intelligence connections to short-circuit Lyndon B. Johnson. And Lyndon B. Johnson had proof, but he didn't expose his data, because he was afraid of the blowback from this guy who was deeply involved in the Intelligence state. Like, "What am I gonna do?" These guys kill presidents.

So you've got Nixon in there, driving the hysteria and madness, and what becomes the groundwork for the neoliberal CIA that we all know and love today. One thing people don't really think about is that the CIA, for so long, was so comically right-wing: filled with knuckle-draggers, cartoonish buffoons, self-obsessed writers of pulp fiction. What happens after Watergate is that it gets very much professionalized from the top down. The CIA is very much a Democratic party asset. You find that people who are on Intelligence panels, they're all Democrats. It has taken not a "leftward" turn, but a liberal one. And I know that you and I don't believe this, but people now really see the CIA and the FBI as the "good guys." You have Robert Mueller being made into an action figure.

The way they are portrayed is as though they were completely unsuccessful. And I do feel that they tried, and fucked up a bunch of shit, but they also were quite wicked.

There's a book called Family of Ashes that's all about how bumbling the CIA is; it's really funny, because it almost reads like it's propaganda by them... they were clearly not completely unsuccessful. They were very successful in some aspects, and still are to this day. The way that it's leaked is very intelligent. The way that the information is handled is very, very coordinated. That's why you have things like, "Oh, they're just bumbling morons: they just dosed people with LSD." You've got this weird narrative being churned. I mean, under Obama, we have a veritable resurgence of the CIA. It's still there. We have, for some reason, this hidden apparatus that is seen as having some kind of valor to it now. But when Tuesday's Child was out in 1969, being an “agent” or “asset” to the CIA was the lowest of the low: it was gross. It was like thug work, almost.

Yet at the top, you have all these byzantine cultural connections. Like, I always want to talk about the CIA and poetry: because the head of Counterintelligence for many years, James Jesus Angleton, was an old Yalie who was a friend of Ezra Pound! He corresponded with him and published him in the Yale poetry magazine.

I was just reading about this.

It's just crazy to me, the idea of these people who are interested in poetry, who clearly come from this perverted, romantic notion, who were running Intelligence agencies. The Intelligence Agencies now are just run by whatever valedictorian technocrat is churned out by Georgetown, or whatever. But it's really crazy to think that this was the psychic territory that Tuesday's Child was doing battle in. The CIA was the enemy: they understood that culture was being weaponized against them and being co-opted, and they were really striving to counteract that, in their own really ridiculous way that I very much love.

I mean, it's kind of crazy: I've been thinking a lot this year about 'unreadability' as a tactic, of self-defense. It's kind of interesting when you see this publications, fanzines, countercultural texts that are really, really niche... the linguistics are really specific, the imagery, the entire way it is presented is really specific, but the specificity kind of belies this quite serious motivation in its writing.

Absolutely. It's very much a sensory overload: it's trying to get that hallucinogenic concoction in its flow of ideas. And it has such a strong visual vocabulary that I think is really fascinating. And it's almost like an idiolect... each magazine has its own editorial voice, its own visual language, its own way of organizing and producing thoughts. It's really quite extraordinary. What's quite fun about Tuesday's Child is, I feel like right now, there's so much preponderance on aesthetics... there's very much a lot of, "How will we be looked at aesthetically? What is our vibe? What is our look? What is our brand?" And Tuesday's Child, every issue looks different. But they keep these markers that let you know you're still in this universe of theirs. Some issues will have a few full-page spreads that are reportage on the Black Panthers. Others will have a spread that's just cartoons. Different issues really bounce ideas off of one another while still at the same time maintaining the same voice. It's really fascinating what they're able to do. And they also report on things that we don't really normally associate with that time. We do in a way... But they do reports on preachers who use leftist terminology and phrases - a feature called "the Jesus Trip" – like preachers dropping lingo in conversations around campuses where they'd try to get kids to join their pseudo-revivalist movements. There are lots of different looks at how the counter-culture is reversed and distorted.

I was thinking about how meta it is, the whole "777 revised" thing – there's the whole foundation of the text looking at how the CIA is infiltrating counter-culture, and then you've got this very famous occultist [in Aleister Crowley] – very influential person, but also, at one moment, probably an operative himself – you know?

They're very eclectic in their materials that they're willing to incorporate and pull together. And some of that is probably just the limited resources they had access to at the time. But also, just generally whatever the editors were feeling. It's interesting too, because one of the writers, Melanie Black, who comes on in issue 3, comes on very strong and writes a lot of original material that kind of harkens back to erotic magic in the occult tradition. I don't want to come off too sophomoric about it all, but you can very much tell they were all enjoying themselves while they were making this. Like, they very much liked what they were doing, if only for a short time. It's very much a project that has a lot of spontaneity and joy to it, even as it covers real and harsh material. It still, I think, is able to have a little fun, that so-called "prankster" tradition you see in Abby Hoffman, etcetera. You don't really see that now. What do we have now? We've got, like, Borat, telling us to vote, or whatever.

I was thinking about that earlier too [laughs]. I was listening earlier to this podcast hosted by the astrologer Anne Ortelee, who does a "weekly weather" report. And she was talking, this week, about the archetype of the psychopomp or trickster, and she went on this anti-Borat rant. And I was thinking, yeah, they're definitely connected... but in a bad way. [laughs]

Tuesday's Child really captures a heyday for that. I think people's personal boundaries were looser in a way that we really couldn't imagine. Just the general permissiveness of things was very diametrically opposed to how we often have to conduct ourselves right now.

Especially during the pandemic. I was watching a show that had an orgy scene in it, recently, and was thinking: "Wow, this is like, triggering now." [laughs]

Exactly! That's something I wanted to talk about, too, because it is rather pornographic to see people unadorned, even in this non-erogenous way.

My friend sent me this Tweet wherein someone said they were "raw-dogging the air," in reference to their not wearing a mask – and I was like, man, it really does feel like that right now.

It's classified now: imagine living in the same house with 30 people...

Yeah, and like, having sex with all of them. This has been really fascinating: I honestly didn't know you were a conspiracy maniac.

That's one way to put it.

I mean, in the best and most skeptical sense. It's really a sad moment, because we're all awash with conspiracy theories right now, but they're all really bad ones: like QAnon, you know?

I could talk about that for so long – the Pizzagate to QAnon pipeline. I've done a lot of reading on that too.

I went to this hippie school very briefly, before I transferred to Temple University, as an undergrad. And everyone who was in my class is a QAnon person now... and they were all leftist farmers. And it's so fucking weird. I can't wrap my head around it.

That's kind of crazy, that's what we're digging into, that's really nuts. 'Cause once it gets leftward, then it's game over.

I think that's the "real conspiracy" [laughs] – I'm like, "QAnon is a psyop!" But I totally think so.

Maybe the meme itself, QAnon, wasn't created as a psyop, but it absolutely has been expertly co-opted by like Michael Flynn and Donald Trump Jr telegraphing it to your uncle or grandma or classmate. It has this anti-establishment, anti-deep state messaging that I think many find attractive now as they did at the time of Tuesday’s Child. So many have been so thoroughly swept up in Q, it's kind of insane. It's like this world-eating behemoth: anything that gets in its path, it's able to absorb, right? I think Trump personally, if he does lose the election, this is gonna become the new Tea Party: the "Q Party." Like, these really misguided people who are led under this inane banner. That's going to become the insurgent factor in politics, I think.

*

Mitch Anzuoni is the executive editor and assistant janitor of Inpatient Press, an independent press based in New York City. You can follow him on instagram @inpatient_press or on twitter @unrealchill.

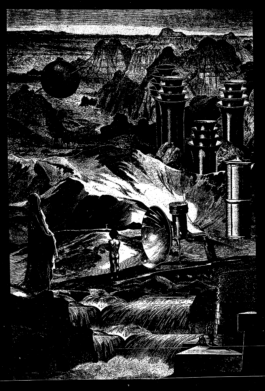

Images scanned from Tuesday’s Child provided by Mitch Anzuoni.

Available here.

“Tuesday’s Child was a short-lived “ecumenical, educational newspaper for the Los Angeles occult underground” published in Hollywood between November 1969 and April 1970. While perhaps not as successful or well-known as The Los Angeles Free Press or The East Village Other, this ragtag weekly nonetheless produced an eclectic and electric array of material: exposes on CIA activity in LA, a run-in with the Coast Guard at Alcatraz, lurid cartoons, demonology lessons, tips on starting your own coven - all threaded in an acerbic, lysergic vein.

Tuesday’s Child is also notable for its decidedly queer stance and heady admixture of sex, politics, and mysticism. Its pages often feature first-hand reportage of happenings in the Greater LA queer community (“GAY POWER STUNS HOLLYWOOD”, Volume 1, Issue 5) as well as copious inches to kinky classifieds, personals, and erotic horoscopes.

Fifty years on, this volume stands as the tabloid’s first complete physical compilation and a fascinating primary perspective on some of the most tumultuous times in American history.”

*

Mitch Anzuoni interviewed by M. Elizabeth Scott in Fall 2020.